«The goal of Jesuit education is the formation of men and women for others, people of competence, conscience and compassionate commitment»

Early years and vocation

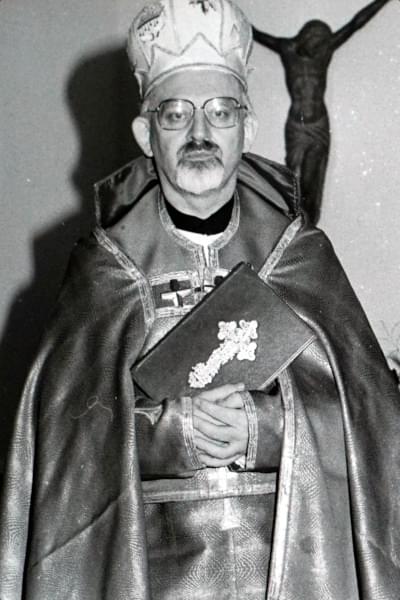

Father Peter-Hans Kolvenbach was born on November 30, 1928 in Druten (Gelderland, Netherlands). His parents were Gerard Kolvenbach (German) and Jacoba Domensino (Italian).

He came to know the Society of Jesus through his secondary studies at Canisius Colle and after a year of studying Latin and Greek, he entered the novitiate at Grave on September 7, 1948. He pronounced first vows on September 8, 1950. After a year of juniorate at Grave and three years of philosophy at the Berchmans Institute of Nijmegen he was sent to Lebanon in 1958.

An expert on the Near East

From the start of his new assignment, he dedicated himself to the study of Arabic through direct contact with people. In his new mission in the Near East, he specialized in the Armenian language and literature.

He studied at St. Joseph’s University in Beirut for four years. The Vicar Apostolic of Beirut, Eustace John Smith, OFM, ordained him a priest in the Armenian Rite on June 29, 1961.

He continued to study philosophy and linguistics in Beirut and Paris. His final year of formation was in Cleveland in the USA, where he completed tertianship. He professed solemn vows on August 15, 1969.

At St. Joseph’s University in Beirut he was professor of linguistics and Armenian language and literature (1968-1974). In 1974 he was named Vice-Provincial of the Near East. He took part in General Congregation 32 (1975).

In 1981 he was called to Rome as Rector of the Pontifical Oriental Institute.

Superior General

He took part in General Congregation 33 as elector of the Vice-Province and elected Superior General on September 13, 1983.

He convoked and presided over General Congregation 34 (1995).

During his long generalate he participated in many Synods of Bishops; he was a member of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life, and Consultor for the Congregation for Oriental Churches.

Back to the Near East and final years

General Congregation 35 accepted his resignation on January 14, 2008 and thanked him in the name of the entire Society for his generous service as Superior General.

At the end of the Congregation, he returned to the Near East Province. In recent years he continued working on various themes related to his specialization in Armenian language and literature.

He died in Beirut on November 26, 2016 after a brief hospitalization.